|

|

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Print this page |

|

|

|

|

|

TRAINEE PILOT. – Ron Raymond.

A lot of people

reading this will remember Ron Raymond, known affectionately to one and

all as “R-Squared”.

Ron, these days, lives in New Zealand and is writing a novel titled “Throw a Nickel” which deals with air combat during the Korean War. He has written the following short story about his early days in the RAAF. |

|

|

A tragedy of mis-spent youth.

I never really intended to become a pilot, not that I had anything against the vocation. It was just that, as a boy, my preference had been a life at sea; to serve as an apprentice deck officer in the merchant navy and eventually rise to command my own ship. That was what I had really wanted to do; in the event I finished up flying in the Royal Australian Air Force - so this is a story about that.

I missed my father, who had died earlier, a circumstance that, while a young bloke, eventually led to my departure to boarding schools, boarding houses and the company of bored youths seemingly hell bent on an appearance in the juvenile court. I have no idea what triggered their frustration but in my case, with nobody to counsel or control me, I simply licked my metaphorical wounds and did whatever took my fancy without further thought: sailing, racing bicycles, wandering the streets ‘looking for fun’, boxing, cricket, rugby; all financed by an overly indulgent grandfather. A totally hedonistic if not irresponsible approach to life; looking back I am surprised that girls played such a minor role in it all, although this is probably understandable as I simply did not have the time or capital to fit them into a programme so full of trivia and self interest; anyway time enough for girls after the really important stuff.

While my grandfather attempted to guide me onto a more conventional path; the guidance fell short of supervised schooling and I duly failed my Queensland Junior Certificate examinations, all except English expression anyway. Mind you I had scored two tries during one august rugby match, won the one mile foot race during my house sports, raced my bicycle successfully on the quarter mile dirt track during the preliminaries at the Brisbane Speedway and acquired a nondescript sailing dinghy that would not point up to windward very well so the really important things in life were catered for.

And

even though it was really all I wanted to do, my widowed mother flatly

opposed my marine aspirations on the basis that the sea was full of

carnivore ready to eat me on sight even though I tried to explain that

most carnivore were land based mammals like lions and tigers rather than

fish, an argument she dismissed with the

Nevertheless, my elders prevailed. I duly completed the prescribed forms and packing a solitary bag to sustain me during my great leap into manhood, I left for the RAAF’s Ground Training School, Forest Hill, Wagga Wagga, where I was confident I would become an Airforce pilot. Unfortunately the Airforce did not teach pilots at the Ground Training School, Forest Hill, Wagga Wagga - it trained mechanics; another fact that escaped me at the time. I thought the Airforce built its own aeroplanes and that everybody, apart from girls, flew those aeroplanes.

The awakening began as I stepped from a hot dusty Airforce truck, onto a hot dusty parade ground, in the middle of an equally hot dusty summer day in the Riverina. A crusty old Flight Sergeant drill instructor barked at my bewildered colleagues and me as we emerged from the vehicle and everybody stood up straight. The Flight Sergeant barked again and we all turned to the right. Another bark and we shuffled off in the direction of the hospital. “Left! Right! Left! Right! Smarten up there. You’re airmen now, or will be when I’m through with you. So let’s see real marching. Head up! Chin in! Chest out! Suck in that gut! Left! Right! Left! Right!” Some of us tried to meet the great man’s expectations, some wondered what on earth he was talking about, and some were reaching the conclusion that they had just made the greatest mistake of their lives. |

|

|

A fisherman traded a sea gull for a sausage – he took a turn for the wurst. Sorry Rupe! |

|

|

Eventually the assembly ambled to a stop – ‘halted’ the Flight Sergeant called it - outside the base hospital where we received a lecture from an ageing medical doctor on the danger of venereal disease, the hazard of irregular bowel movements, and the virtue of circumcision. Most of us were intrigued that the first step in a military career involved a harangue on VD when we could barely spell it. We were then formed into a queue, single file the Flight Sergeant called it, and individually led into a surgery for vaccination, inoculation and a medical examination. Without knowing what was coming, I approached the medical with mild enthusiasm: if anything was wrong with me perhaps I would be rejected and allowed to go to sea after all. Unfortunately my hopes were dashed when I passed the examination with flying colours. In fact I don’t doubt that I could have arrived comatose and still passed - fitness seemed confined to body temperature: you passed if you were warm, there was no escaping the clutches of the Airforce at that late stage.

At least the process was brief. The doctor studied my tongue while I said “Ah!” listened through a stethoscope while he tapped my chest; checked my blood pressure; peered into my eyes with a light; held my testicles while I coughed, and made me pee into a bottle. “Multiple moles on body,” the man declared to an orderly noting detail on a clipboard, “Next!”

I dressed as quickly as I could and wandered aimlessly through the sole exit from the surgery. “You there!” the Flight Sergeant bellowed at me from a distance of four feet as I emerged into the heat, “Get your ‘air cut!”

“Hair cut?” “You ‘erd me. Get your ‘air cut. That queue over at that hut. Join the queue and the barber will cut your ‘air!” |

|

|

|

|

|

Apprentices of Hut 103 January 1950. Ron Raymond, second from right between Bushy Trimble and Tony (Bodgie) Garman. |

|

|

I studied a line of recruits standing disconsolately in the blazing sun waiting their turn to ‘ave their ‘air cut.’

“Yes Sir,” I replied obediently. “And don’t call me Sir. I’m a Senior NCO not a bleedin’ officer. The NCO’s run this Airforce make no mistake about that, and Flight Sergeants are the most senior of the Senior NCOs. You can’t count Warrant Officers; they are almost officers even though they live in the Sergeant’s Mess. Now do you know what a Senior NCO is lad?”

I felt quite confused over the complexity of the pecking order described by the Flight Sergeant.

“One of the officers who run the Airforce?” “No, no, NCOs are non-commissioned officers. An officer holds the King’s Commission.” “Yes Sir.” “Don’t call me Sir I said. Call me Flight Sergeant if you must speak to me at all.” “Yes Flight Sergeant.” “Good.” “Excuse me Flight Sergeant.” “What now?” “May I ask a question?” “Of course lad; go ahead.” “When do we start learning to fly?”

“Gawd spare me bloody days. When do we start learning

to fly the man said; I’ll teach you to fly me

I remember joining the queue waiting outside the barber‘s room. Hitler had a lot to answer for when he shot down that Hawker Hurricane.

Entrance to RAAF Wagga today.

Despite the drill instructors, the tedium of military routine, the discipline, and restrictions to my personal freedom; I settled into the life of an apprentice aircraft mechanic readily enough. I actually developed an interest in aircraft, even if I was never going to fly one. On the negative side, I found the syllabus obsolete; the training equipment archaic; the food monotonous, and the Wagga Wagga girls openly contemptuous of poorly paid RAAF erks in general and engineering apprentices in particular.

On a more positive note I spent three years learning to march; how to make a regulation bed roll; to hack the scale off cast iron with a cold chisel; to file a piece of steel square; to drill a straight hole, and to tap a thread through the hole. They taught me how to weld; to work a lathe, and all I needed to know about hollow rivets that held Hawker Demon biplanes together during the 1930s. As a bonus I learnt to hand stitch fabric to the wing ribs of a Tiger Moth, to trim its rigging by adjusting the flying and landing wires, to hand swing a propeller without losing an arm, and how to take a worn out Dakota transport aircraft apart. All very good stuff, but a totally inappropriate preparation for my ultimate posting to a jet fighter squadron and aeroplanes I had never seen in my life.

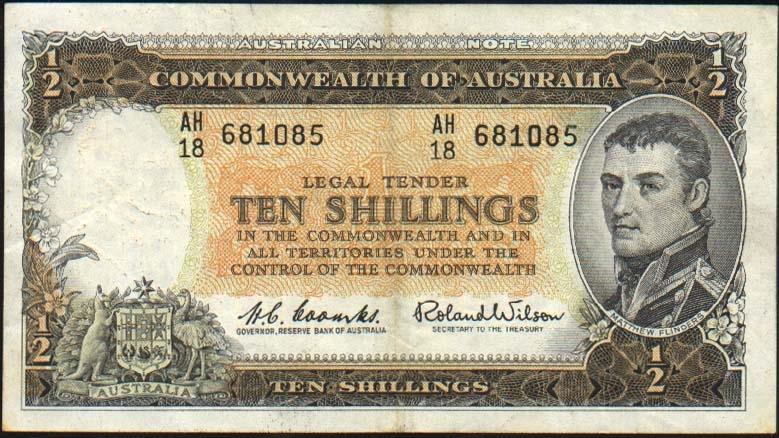

Our fortnightly pay as

apprentices totalled five shillings (50¢), sufficient for one chocolate

and attendance at the

After graduation I quickly found that life in a fighter squadron was not confined to maintaining the aeroplanes. There was a variety of extraneous tasks to punctuate an otherwise sensible routine: physical training, guards of honour, ceremonial parades, kitchen duties, general cleaning, emu parades the service called them, compulsory sport and guard duty. In fact the intensity of trivia prompted my attempt at selection for pilot training. The bitter cold and isolation of guard duty reinforced the decision.

I was on guard duty and had been assigned to foot patrol, sloshing my way around a beat until midnight; hunched deep into a greatcoat in search of protection from the rain and cold; my rifle slung inverted by its shoulder strap to prevent water entering the barrel. The night was total; pitch black, as dark as the inside of a coal miner’s sock. I was miserable, tired and hungry. My boots were soaked. My feet were cold. My fingers felt frozen and my throat burnt in response to an imminent cold.

Each time I passed the Sergeant’s Mess I could see into the anteroom, into the bar. I paused and watched the men grouped around the fireplace warmed by the flames; joking, laughing; enjoying the very basics of life: shelter and warmth. Things everybody took for granted; everybody except A33756 Leading Aircraftsman Ronald George Raymond, shivering, sniffing and fighting the threat of pneumonia. I studied the group. Most were pilots, a logical enough circumstance with the weather the way it was: a wet maritime southerly eliminating all hope of flying during the next 48 hours. They could afford to relax while I protected them; stood between them and the real world, the combined threat of saboteurs and partisans perhaps even the Chinese army itself. Of course nobody, not one of them, appreciated their debt to a humble mechanic. A dribble of ice cold water trickled from my beret, over my face and under the collar of my greatcoat. I sneezed, sniffed and sneezed again. That did it: no more mooching about in the cold and the rain, having to clean and oil my rifle before I went to bed. No more half warm tea in a bleak guard house. No more undressing in the cold and the dark; avoiding noise for fear of waking sleeping colleagues. I determined to be out of there - I was going to be a pilot and take my place in front of that fire. |

|

|

Old Air Force saying – “If you see an armourer running, follow him”.

|

|

|

I was waiting at the Orderly Room door when the Squadron returned to life the next morning. My application for pilot training was in the hands of the Adjutant twenty minutes later. After ten days I was ordered to present myself at the hospital for another round of medical checks. From there I poured over an unintelligible assortment of numbers and squares and circles at the education section; wrote an essay on why I desperately wanted to become a fighter pilot, and then returned to the maintenance hangar to await the outcome. After two weeks I was called before the Adjutant once again. “Your intelligence test leaves a bit to be desired,” the Officer said.

“How’s

that Sir?” I replied. I had mixed feelings about my intelligence; I had

been clever enough to pass my

“Speed and accuracy at routine,” the Adjutant continued. “It says here your score at routine tasks is way down.” The man pointed to a column of squares on a piece of green paper. The evidence was damning. The ‘Accuracy at Routine’ squares stopped well short of the other criteria. “What does that mean, Sir?” “I don’t know son. The Education Officer knows all about these things, I’m just an air gunner.”

The Adjutant paused and studied the offending squares; looked up at me standing at attention before his desk, and returned his eyes to the paper. “It probably means you wouldn’t make a very good bank teller or equipment clerk I suppose.” “No, I don’t think I would make a very good bank teller,” I agreed. “I think I’d be a good pilot though, I can fly a Tiger Moth already - I’ve got 100 hours. I also thought of becoming an air gunner, but you need very good eyes and quick reflexes for that,” I added diplomatically.

“It’s nothing really,” the Adjutant replied, modestly. “Comes automatically after a time.”

The officer studied me once more while he considered the matter. He obviously decided that I was probably what the Service wanted. Medium height; clear eyes; fair hair; well built and fit. I spoke well enough, wore my uniform neatly, and had good reports from my section commander: excellent cannon fodder actually. “Damn it man, you seem bright enough, certainly as intelligent as I am,” the Officer decided aloud. He inked in two more squares in the Speed and Accuracy column; shoved the piece of paper into a file marked Pilot Applicants and nodded his confirmation that the meeting was over. I saluted and left the office. I needed to disappear before my new found mentor changed his mind.

|

|

|

Another old Air Force saying – “The only time you have too much fuel is when you're on fire.”

|

|

|

After that the selection process went smoothly enough. Apart from ‘multiple moles on body’ the medical did not reveal any abnormality. I lied to anybody who would listen concerning my unbridled passion for fighters. I studied furiously to further my aeronautical vocabulary and my understanding of air combat. I broadened my knowledge of aircraft structures, aerodynamics and gunnery before finally presenting a massive bluff to the interview board concerning my enthusiasm for life in the RAAF. I doubt that The Board believed a word I said, but they probably agreed that anybody who went to all that trouble was worth a try. Years later I learnt that the board had rated me immature but as the Battle of Britain was won by a handful of equally immature 19 year olds I would probably do at a pinch; anyway there was a war on in Korea and the RAAF was losing fighter pilots at an alarming rate.

By the time I had read and studied and bluffed my way into aircrew, I had also convinced myself that flying military aeroplanes probably was not such a bad way to go anyway. Six months later, A33756 Trainee Pilot Ronald George Raymond found himself strapped in the open cockpit of a Tiger Moth above RAAF Base Uranquinty, Wagga Wagga, in the middle of winter. My feet were numb, my fingers were frozen and my nose was running from the blast of cold air thrown in my face by the slipstream. I felt as if I wanted to sneeze. ‘Oh shit,’ I thought, ‘absolutely nothing’s changed!’ |

|

|

RAAF Pilot training in

the fifties was not without its excitement, not that I had expected

anything less or even thought about it much for that matter. My pilot

logbook includes initial theory and basic aircraft handling of 90 hours on

the Tiger Moth and Wirraway at Uranquinty with a further 100 hours

advanced training on the Wirraway at Point Cook in Victoria; advanced

training comprised formation flying, instrument flying, air to air

A friend, quiet, unassuming, Bill Muir had an engine fail on takeoff during his first solo flight;

“Wow Bill that must have been quite a first solo?” “Really there wasn’t that much to it, once the engine quit it was just a matter of landing somewhere. There was no decision involved; straight forward stuff actually.”

Not to be outdone a RAAF trainee landed in the wrong lane and collided with my machine; cutting the tail off, chopping out the plywood turtle back and the tube steel sub-frame before chopping the back out of my seat and finishing on top of me - literally. Fortunately its propeller had been well and truly trashed before jamming me in my cockpit. Once again I was pleased that the Tiger’s fuel tank was high on the top wing, clear of any damage, clear of any fire risk.

I finished that day in the base hospital for my troubles, a circumstance that so alarmed my pregnant wife that she convinced a friend to drive her to the flying school to check my condition. This was not her best idea that day for the friend duly rolled his car and we all ended up in hospital together although thankfully without much by way of serious injuries. All of which revealed my married status to the Commanding Officer at a time when it was forbidden for trainee pilots to wed. Years later I was to review and condemn an assortment of obsolete files from the Uranquinty archives at the time of our air training. While the crash and loss of two aeroplanes was dismissed as a natural hazard of air training, after all, trainees will be trainees, the fact that I had the temerity to marry during the interval between my interview and arrival on course seemed tantamount to the gunpowder plot. That I was running top marks on the Tiger Phase was about all that saved my skin.

The Wirraway was quite a step up from the biplane. Originally designed

as a fighter, it seemed a steal from the American Harvard, although with a

more powerful radial engine; it could be a treacherous gadget to land. The

Similarly there was a trick to the hydraulic system in the form of a pressure control valve (PCV). The valve had to be pushed in to direct fluid pressure into the system; this pressure was required to force the flaps down against the airflow and pull wheels up against gravity. Of course Murphy’s Law says that any procedural ambiguity will trap somebody sooner or later and here the trap involved selecting gear down, feeling the satisfying clunks as the wheels locked into place then forgetting to push the PCV in after selecting flap when the aircraft lined up with the airfield. The machine duly became very high on its approach; a situation mandating a go-around, a manoeuvre that involved selecting the wheels up and pushing the PCV in at which stage the wheels came up but, because the flap-handle was still in the down position, the flaps went down. I watched a Wirraway barely clear the trees at the Uranquinty boundary while a thoroughly bemused trainee struggled to work out just what on earth was going on. Of course these were the days when men were men: we either landed with full flap or none at all; partial flap was strictly for girls. The German Stuka dive bomber had nothing on a Wirraway glide approach with full flap and gear down.

Finally the reverse sense of the mixture control was the last straw, catching one of our chaps when he pushed the mixture lever forward instead of the throttle during a go-around and producing absolute silence from the front of the aeroplane. Interestingly the manoeuvre was not without elegance, as the aircraft settled on its belly with aplomb and minimal damage. Later, after we had graduated as sergeant pilots, I met Nobby at our storage depot at Tocumwal when he taxied in with a wingtip bent and busted during a wing-drop landing after a delivery flight. I guess he must have held off with ‘the nose above the three point attitude’; I did not have the heart to ask him if that was the cause or how he felt about the Wirraway in general.

My lady and I were plagued by poverty during the trainee pilot days and for a time thereafter. The struggle to finance my flying, contribute to my Tiger Moth smash, maintain a recalcitrant motor cycle on the road and indulge a growing passion for gliding soaked up anything that I earned for a time. I met Lyn (Lyndel Joan Moore) at a family party after a three or four hour drive from Sydney to Newcastle. The drive, like most things that we did in those days, was quite a flamboyant exercise in a soft top Ford Anglia that required every one of its 10 horse power to climb even a moderate grade with four twenty year olds on board. Any power inadequacy was corrected by the driver applying half choke and taking a running pass at things, while cornering stability was enhanced by the passengers leaning out of the vehicle to keep it upright in the best sailing skiff tradition. Lyn and I duly married after an eighteen month courtship, rented a room in Wagga when I went on Number 23 Pilots Course and struggled with money and the intricacies of military aviation thereafter. Our son, Ric, was born at Wagga. Towards the end of the Uranquinty phase of training we moved to Melbourne for Applied Flying. Actually positioning on the various transfers was probably the most hazardous part of life at the time. The journey to Point Cook was completed in a friend’s V8 Ford Coupe that provided a definite improvement in power and stability while lacking mechanical reliability; the tie rod joining the two front wheels persisted in falling off at the most inconvenient moments (even in Melbourne peak hour traffic on one momentous occasion) denying the driver use of both wheels to steer around corners. None of which phased the owner, Harry Morgan, who carried a hammer to bash things back into place whenever the situation arose.

I don’t know if

‘H’, as he was known, used Lyn and me as a precedent however he and his

lady, Heather, also married while we were on course; we finished up

sharing a three bedroom flat in Essendon becoming close friends in the

process. Harry was an amusing character, an accurate shot and an

unassuming pilot who was far better than he would have people believe. He

occasionally suffered severe nose bleeds and I once saw the top of his

flight suit covered in blood after a Wirraway flight at Uranquinty; I do

not know if this was cured before he started flying fighters – surely it

must have been. Nevertheless I always wondered if it was a factor in the

Sabre crash that killed him shortly after graduation. It seems that he

misread his altimeter by 10,000 feet and flew into a mountain during his

subsequent descent. Of course those were the days of ‘three point

altimeters’, diabolical (It is easy to see where confusion can arise, the 3 point altimeter at left is indicating a level of 10,180ft whereas the digital one on the right indicates, clearly, 5,260ft - tb)

Marriage to an Airforce

pilot, certainly an NCO and certainly a trainee, was hard on ladies. While

pay was minimal and benefits few, families were generally left to their

own devices, finding their own accommodation in strange cities every two

or three years, arranging schooling, doctors, developing new friendships

and assuming new responsibilities while supporting their husband in a

risky career. Additionally, the instability usually made home ownership an

impractical dream; even if people had the money to purchase a house.

Whenever the husband was deployed away or otherwise committed, the lady

did it all on her own; a difficult situation that was complicated further

if the family did not own a car, as was the case during our early married

life. Renting a reasonable house or flat was invariably a struggle

although the RAAF eventually provided some relief through a temporary

accommodation allowance to tide us over until a suitable, affordable

rental could be

Lucky indeed was the family that was awarded a ‘married quarter’, certainly one with the low rentals prevailing on the air base proper. There was always underlying concern over the hazards of the game. The best pilots, and those who wanted to star, flew the hottest aeroplanes at a time when we were still learning the science behind very high speed flight. Some wives handled the stress with grace and dignity; some did not but should not be accused of any weakness; it was a difficult life for a woman. My lady and I often joked of the risks;

“How will I know if you have crashed?” “Easy, somebody will knock on the door and ask for the Widow Raymond.”

Unfortunately the joke backfired when a colleague, John St Moore, called on her after a fatal at Point Cook to advise that I was OK but could not be contacted as I was still flying. When Lyn opened the door in response to John’s knock he asked, “Ron Raymond’s wife?” To which Lyn replied innocently, “The Widow Raymond you mean?”

I can only take my hat off to that lady, or at least to the memory of her, but that’s another story.

The particular crash that I refer to, out of context I am afraid, involved Graham Scutt and a student during my first tour as a flying instructor at the Basic Flying Training School, Point Cook. There was an element within the RAAF advocating turn-back manoeuvres should an engine fail shortly after takeoff. Personally I was against the exercise; pointing out that we were killing more pilots practicing the turn-back than we saved in emergencies and that pilots had landed straight ahead ever since Louis Bleriot ditched during mankind’s first attempt to fly across the English channel. Unfortunately the voice of a ‘sprog’ instructor, and a mere flying officer at that, was drowned in the enthusiasm for something perceived as a life saver: so Graham went on to an early grave. Sadly he actually survived the smash; the crash crew could see him making a dazed and uncoordinated effort to escape the cockpit however the rescuers were unaware of the procedure to open the heavy canopy and the fire spread before the pilots could be freed. Equally sadly the Senior Air Traffic Controller, ‘Spec’ Taylor, who tried to assist the crash crew, took the affair to a guilt ridden grave; an absolutely unnecessary responsibly after a brave but futile attempt to save the crew.

Graham had been elevated to a peak of glory after a heroic attempt to shoot down the first Sputnik which was launched into orbit during the Cold War. While an awed gathering of NCOs peered at the Russian wonder beeping and soaring above the RAAF Richmond Sergeant’s Mess, Graham took a more positive attitude to the intruder and fired a muzzle loading blunderbuss at it. Not only did he fire the gun, he woke everybody sleeping in his immediate vicinity and alerted the Orderly Officer that something was awry on the Base; the great man quickly appeared on his bicycle to be confronted by assorted NCOs either slinking into the night or assuming disinterest in the whole affair, while Graham attempted an air of innocence despite a dusting of carbon on his face and shirt and smoke wisping from the barrel of the antique weapon. As history has it he failed to hit the satellite; somebody said that he did not allow enough deflection.

Advanced training at Point Cook was a far more serious business than Uranquinty. With its proximity to RAAF Support Command in Melbourne; with its history and tradition it was mired in dignity and old world charm. The buildings were pre-war brick structures, the hangars on the southern tarmac (by the shore of Port Phillip Bay) bore scars of accidents dating back to the early ‘20s and the messes, particularly the Officer’s Mess, were steeped in protocol. The First Half Flight formed there ready for its departure for Mesopotamia during World War One; pilots were taught to fly wood and rag aeroplanes that were wonders of man’s determination to kill himself while the roads were lined with picturesque pine trees poised to snare any pilot who might have escaped the frequent engine and structural failures so common at the time. Readers would be justified in seeing all this as a wistful memory and they would be correct. ‘The Point’, as it was known, holds so many memories for those of us who served there.

Perhaps weapons training was the unique feature of advanced training; not that this is dismissive of pure flying aspects however dive bombing, air-to-air cine and gunnery were far more adventurous than instrument, formation or night cross-country tasks. Weapons exercises are the stuff that combat pilots are made of and all of us, with the exception of two, wanted our Airforce wings. Predictably ‘the two’ were looking to use the RAAF as a stepping stone to airline careers and as graduation drew near they proceeded to fail their various flight checks. The ploy was about as subtle as a blunt axe and service administrators quickly became aware of the situation; the trainees were suspended from training and, to their horror, offered a choice of menial non-flying appointments. It did not take long for the lads to have a change of heart and they soon started passing their tests once again. Very few people associated with number 23 Pilots course had much by way of sympathy for them.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Number 23 Pilot Course graduation group. Ron is in the back row second in from the left between Zane Sampson and John Tribe. |

|

|

|

|

|

Two applied manoeuvres illustrate the nature of our advanced training; the high quarter attack on a stooge aircraft and the dive bombing pass. The stooge was a target Wirraway, cruising slowly with a touch of flap while the aggressor rolled into the attack from a higher altitude. The attack dive became a curve of pursuit at increasing speed with the attacker finishing up behind and rapidly overtaking the stooge. The final stage involved a steady hand holding the central pip of the reflector gun sight on the junction of the stooge’s stabiliser and fin while a cine picture was taken followed by a vigorous bunt to pass under the stooge at the last possible moment. A really exciting attack actually shook the stooge when the attacker barely cleared it during the bunt. I still wonder that the attacks were not broken off at a specific range from the stooge, a distance judged by the range ring on the gun sight; there would have been greater training value and a safer break in that fashion. To this day it surprises me that there were no collisions, I had learned about acceptance of risk early in aviation: that sooner or later, one day, it would ‘get you’ just as it did when I was repeatedly flying my Tiger Moth at those gum trees in the paddock outside Wagga Wagga.

Dive bombing was all

excitement. The target was approached from about 1,000 feet at right angle

to the

It was important to promptly pull up from the dive straight, wings level. Any attempt to roll and see the result of the attack during the initial pull up risked over stressing the wings during a manoeuvrer termed ‘rolling with G’; one instructor did just that shortly after we left Point Cook, sadly he pulled his wings off and crashed at high speed.

Throughout my time in the military the ‘powers that be’ kept sending us on ‘Survival Exercises’. I had experienced these as an apprentice, as trainee aircrew at Uranquinty and finally at the end of our applied phase at Point Cook; by which time I was heartily weary of them. At The Point, we were weighed in the name of research before being loaded into a truck and dropped by the roadside two days walk from home.

Of course the idea was to live off the land, develop survival skills and make our way back cross country. Half an hour later we were still by the side of the road arguing over the relative merit of audacious and cunning plans when a farmer stopped to check if we were in difficulty and, having listened to a tale of hardship, and agreeing that most senior officers did not have a clue about handling men (he had been in the AIF during the big war) offered us a lift as far as he was going - namely the village of Little River. Little River proved to be an ideal venue for a survival exercise; it was within striking distance of Point Cook, had a quaint little pub, an excellent restaurant and an empty school building to bed down for the night. All-in-all an agreeable arrangement complete with a first class meal, a riotous evening with a group of locals in the pub and the offer of free transport to the gates of Point Cook in the morning. I have forgotten how much I had gained during my final weigh-in, but I do know that it was significant.

And then it was all over. We cleaned our webbing, formed up as a flight on the parade ground, received our wings, listened to various speeches, advanced in review order, saluted the reviewing officer and marched off in column of route to the strains of Auld Lang Syne. We changed into our new sergeant’s uniforms and joined our guests in the Sergeant’s Mess for afternoon tea. Lyn, Heather, Harry and I had our photographs taken holding Ric, my son, for the local newspaper and I wondered if 23 Pilot Course would ever gather as a group again. In the event we never did; the airline twins jumped ship at the earliest, occasionally a couple of us might bump into each other, some of us were killed, some fell by the wayside in the course of our military careers but most of us completed operational tours and the occasional desk job before leaving the Service with the onset of age and senility; which really was no more than could be expected.

|

|

|

Three blondes died in a car crash trying to jump the Grand Canyon and are at the pearly gates of heaven. St.Peter tells them that they can enter the gates if they can answer one simple question. St. Peter asks the first blonde, "What is Easter?" The first blonde replies, "Oh, that's easy! It's the holiday in November when everyone gets together, eats turkey, and are thankful..." "Wrong!, You must go to HELL" replies St. Peter, and proceeds to ask the second blonde the same question, "What is Easter?" The second blonde replies, "Easter is the holiday in December when we put up a nice tree, exchange presents, and celebrate the birth of Jesus." St. Peter looks at the second blonde, bangs his head in disgust on the Pearly Gates, tells her she's wrong and to go to HELL, and then peers over his glasses at the third blonde and asks, "What is Easter?"

The third blonde smiles confidently and looks St. Peter in the eyes and says, "I know what Easter is. Easter is the Christian holiday that coincides with the Jewish celebration of Passover. Jesus and his disciples were eating at the last supper and Jesus was later deceived and turned over to the Romans by one of his disciples. The Romans took him to be crucified and he was stabbed in the side, made to wear a crown of thorns, and was hung on a cross with nails through his hands. He was buried in a nearby cave which was sealed off by a large boulder." St. Peter smiles broadly with delight. The third blonde continues, "Every year the boulder is moved aside so that Jesus can come out... and, if he sees his shadow, there will be six more weeks of winter." |

|

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Forward

|

He was on number 23 Pilots Course at

He was on number 23 Pilots Course at

Friday

night movies on the base each week. The Airforce looked after the rest;

tooth paste, soap, razor blades, uniforms, meals, accommodation and

occasional transport home; all provided we wrote a weekly letter to our

parents, a formality the service took seriously enough to march our

complete squadron to the apprentice mess on Monday evenings; call the roll

to confirm our individual attendance and order us to ‘sit and write!’. Our

names were duly marked off as we handed our letter to the NCO noting the

fact on a special form.

Friday

night movies on the base each week. The Airforce looked after the rest;

tooth paste, soap, razor blades, uniforms, meals, accommodation and

occasional transport home; all provided we wrote a weekly letter to our

parents, a formality the service took seriously enough to march our

complete squadron to the apprentice mess on Monday evenings; call the roll

to confirm our individual attendance and order us to ‘sit and write!’. Our

names were duly marked off as we handed our letter to the NCO noting the

fact on a special form.

mechanics training, even achieve quite good marks in the final

examination, however I had been dumb enough to join the Airforce in the

first place.

mechanics training, even achieve quite good marks in the final

examination, however I had been dumb enough to join the Airforce in the

first place.

instruments

that brought so many of us to a sticky end. I even misread one in a

Vampire jet during an instrument descent on one occasion; fortunately I

levelled 10,000 feet too high and quickly saw my error. I even miss-set

one in my sailplane over 40 years later. The manufacturers eventually

developed digital altimeter readouts for air transport and high

performance aircraft as a solution to the problem. Flight management

computers and modern ‘fly by wire’ machines take most of the grief out of

this sort of thing now.

instruments

that brought so many of us to a sticky end. I even misread one in a

Vampire jet during an instrument descent on one occasion; fortunately I

levelled 10,000 feet too high and quickly saw my error. I even miss-set

one in my sailplane over 40 years later. The manufacturers eventually

developed digital altimeter readouts for air transport and high

performance aircraft as a solution to the problem. Flight management

computers and modern ‘fly by wire’ machines take most of the grief out of

this sort of thing now.  found. Naturally applicants for TAA, as it was termed, had to meet a

battery of ongoing conditions. Some of the rental accommodation was

appalling; we once encountered a council employee in Townsville who

purchased condemned houses then rented them back to the public; Airforce

families in particular. We rejected one place after centipedes crawled out

of taps on the wash tubs – even though it contained a resident kitten that

promptly charmed our son. Things became easier with seniority and rank,

however the burden associated with frequent postings was always there.

found. Naturally applicants for TAA, as it was termed, had to meet a

battery of ongoing conditions. Some of the rental accommodation was

appalling; we once encountered a council employee in Townsville who

purchased condemned houses then rented them back to the public; Airforce

families in particular. We rejected one place after centipedes crawled out

of taps on the wash tubs – even though it contained a resident kitten that

promptly charmed our son. Things became easier with seniority and rank,

however the burden associated with frequent postings was always there.

Unfortunately

the Winjeel turn-back was not the only fatal at that time. Two trainee

instructors were killed during an actual turn-back in a Vampire 35 (a two

seat variant) at the Central Flying School, East Sale, Victoria. Although

the pilots had shut down the engine, engineers could not find any evidence

of a failure and it was assumed that they mistook condensation from the

air-conditioning system for smoke. The aircraft hit the ground short of

the aerodrome boundary and broke up when it struck a ditch.

Air-conditioning mist was a characteristic of Vampire 35s; in fact I often

saw the same harmless phenomena pouring from the vents on Boeing and

British Aerospace airliners in a later life. The sad thing about that

fatal was the futility of it all: the engine was fully serviceable and

operable the whole time. Mind you I had seen the result of an engine fire

in a Vampire at Williamtown. The fire had almost completely burnt through

the left tail boom; fortunately the pilots declared an emergency and just

made it back to the airfield in time: there were no ejection seats in

those early jets.

Unfortunately

the Winjeel turn-back was not the only fatal at that time. Two trainee

instructors were killed during an actual turn-back in a Vampire 35 (a two

seat variant) at the Central Flying School, East Sale, Victoria. Although

the pilots had shut down the engine, engineers could not find any evidence

of a failure and it was assumed that they mistook condensation from the

air-conditioning system for smoke. The aircraft hit the ground short of

the aerodrome boundary and broke up when it struck a ditch.

Air-conditioning mist was a characteristic of Vampire 35s; in fact I often

saw the same harmless phenomena pouring from the vents on Boeing and

British Aerospace airliners in a later life. The sad thing about that

fatal was the futility of it all: the engine was fully serviceable and

operable the whole time. Mind you I had seen the result of an engine fire

in a Vampire at Williamtown. The fire had almost completely burnt through

the left tail boom; fortunately the pilots declared an emergency and just

made it back to the airfield in time: there were no ejection seats in

those early jets.

planned dive path. Almost abeam the target the aircraft was pulled up into

a wingover to place the machine in a dive without involving negative ‘G’,

the gun sight pip was steadied just below the target and held with

increasing forward pressure until the release point when pressure on the

control column was eased to release ‘G’ forces and steady the pipper on

the target at which point the bomb was released. It was important to

release the bomb at the correct height, too high and it would miss, too

low and there was a risk of the aircraft crashing.

planned dive path. Almost abeam the target the aircraft was pulled up into

a wingover to place the machine in a dive without involving negative ‘G’,

the gun sight pip was steadied just below the target and held with

increasing forward pressure until the release point when pressure on the

control column was eased to release ‘G’ forces and steady the pipper on

the target at which point the bomb was released. It was important to

release the bomb at the correct height, too high and it would miss, too

low and there was a risk of the aircraft crashing.