|

Radschool Association Magazine - Vol 28 Page 12 |

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Print this page |

|

|

|

Long Tần.

This Article was printed in The Australian Newspaper on the 30th April 2009 and was sent to us by “Dutchie” Foster.

The Battle of Long Tần was fought between the Australian Army and Viet Cong forces in a rubber plantation near the village of Long Tần, about twenty seven kilometres north east of Vung Tau, on 18th August 1966. It is arguably the most famous battle fought by the Australian Army during the Vietnam War.

Late in the afternoon of August 18, 1966, as the Battle of Long Tan raged at a nearby rubber plantation, Australian Army Commander Brigadier David Jackson grew more agitated by the minute at his headquarters at Nui Dat.

A few kilometres from the Australian base, 120 men from Delta company, 6th battalion Royal Australian Regiment (6RAR), pinned down, were fighting for survival. They were about to run out of ammunition and in grave danger of being overrun by a 2000-strong force that included Vietcong fighters and a crack North Vietnamese army battalion.

"I am about to lose an entire company. What the hell's a couple of choppers and a few more pilots?" an angry Jackson shouted at the RAAF's taskforce air commander, Group Captain Peter Raw. Because of a heavy tropical downpour over the area, Raw had demurred when Jackson requested an urgent ammunition resupply operation using two helicopters from 9 Squadron. He was worried not just about the weather but about the potential risk to his pilots.

While the Battle of Long Tan hung in the balance and Raw hesitated, a young Australian flight lieutenant, the RAAF's most experienced Bell UH-1B Iroquois pilot, Bruce Lane, took the initiative.

"I said, 'Well, I am going anyway.' I wasn't captain of the aircraft. But I probably had more time on Iroquois than anyone else. I would have flown on my own," Lane told The Australian this week. "It was a very heavy thunderstorm, poor visibility with low cloud."

Raw then reluctantly authorised the mission and Lane and his fellow pilots went off to load the precious ammunition. Lane was sure the RAAF would lose at least one Iroquois and insisted that both helicopters be loaded with ammunition, just in case.

Just before 6pm the two Iroquois were airborne, the first piloted by Flight Lieutenant Frank Riley with co-pilot Bob Grandin (right) and the second by flight lieutenants Cliff Dohle (recently deceased) and Lane. Lane's machine, laden with nearly half a tonne of ammunition, was the first to drop its precious cargo to Harry Smith's Delta company in the fading light just five minutes' flying time from Nui Dat.

"We flew at 30 feet and after about five minutes we came to a hover. People in the back just pushed the ammunition out. We were as low as comfortable," Lane recalls.

The ammunition arrived in the nick of time, saving Delta Company from annihilation. Riley was awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross for the mission but Lane's initiative and courage, like those of so many of Smith's troops on the ground, went unrecognised by officialdom. Nearly 43 years later, the story of the Long Tan resupply mission and the saga surrounding the RAAF Iroquois squadron's role in supporting the Australian Army in Vietnam still stirs passionate debate among army and air force veterans as well as war historians.

|

|

In the movies - A man will show no pain at all while taking the most ferocious beating but will wince whenever a woman tries to clean his wounds.

|

|

The story has had profound consequences for the RAAF and the army, consequences that are still unfolding and will continue to resonate for years. Arguments over how well prepared RAAF units were for war in 1966 echo the ones about the preparedness of army and RAAF aviation assets, including helicopters, for combat operations in Afghanistan.

Views of the RAAF's battlefield helicopter experience in Vietnam, however distorted, have also shaped perceptions in US military circles about the appetite of the RAAF to engage fully in wartime combat operations.

Exactly 20 years after Long Tan, in 1986, Australia's army chiefs succeeded in wresting ownership of the battlefield helicopter fleet from the air force. That was a bitterly contested decision strongly opposed by RAAF chiefs. The army's view is that it needed to integrate the helicopters into its order of battle as an essential element of evolving land warfare doctrine.

Historians agree the army's view about controlling battlefield helicopters was directly influenced by its experiences in Vietnam with RAAF and US Army helicopter pilots.

For the RAAF and its helicopter crews who fought in Vietnam, it is the pervasive myth fashioned largely out of the events surrounding Long Tan in August 1966 that has been most hurtful. The rumour, first aired at the time, that 9 Squadron had refused to fly in support of Smith's D company, has proved impossible to dispel.

RAAF 9

Squadron veterans also take issue with recently published Vietnam War

histories, including Paul Ham's 2007 bestseller Vietnam: The Australian

War. "Accustomed to US pilots swinging in to help on call, the Australian

infantry at first maligned the RAAF pilots as cowards," Ham writes.

Acknowledging the many courageous missions flown by 9 Squadron, Ham says

the RAAF's alleged reluctance to undertake certain

Ray Scott, 9 Squadron's commanding officer in Vietnam during 1966, says the squadron never refused to carry out a mission requested by the Australian taskforce HQ during the time he was in command.

"The lie that No 9 Squadron would not operate in insecure LZs (landing zones) and lacked courage is particularly galling. Some members of the squadron gave their lives attempting to support army personnel in insecure areas," Scott says.

Scott has pointed out that 9 Squadron had to scramble to adapt to the rigours of fighting in Vietnam. Only 12 weeks elapsed between the announced deployment of the Australian taskforce to Nui Dat and the arrival of the squadron. Essential equipment had to be scrounged and initially crews were inadequately protected from close ground fire.

The unit carried 414,818 personnel and 4,357 men were medivaced. Only three army personnel died while flying with the RAAF during its five-year deployment in Vietnam.

Another former 9 Squadron officer, Hedley Thomas, says Ham and other writers have overlooked his unit's critical role in inserting and extracting Special Air Service troops in covert operations.

"There was an exceptionally strong bond between the men of the SAS and the air crews of the squadron, and it exists to this day," Thomas observes. "We always got them out, night or day, regardless of the diabolical situations they were often in. I estimate that about 200 or so extractions were performed while the SAS (was) in contact with the enemy. On each one, the pilots knew before starting their approach they would be under fire while on the ground or in the hover. Cowards do not deliberately fly into hot areas."

In the movies - Kitchens don't have light switches. When entering a kitchen at night, all you have to do is open the fridge door and use that light instead.

Retired defence force and army chief General Peter Gration, who served in Vietnam, says there was a policy, "rightly or wrongly", that 9 Squadron would handle its helicopters differently from the US Army, which lost 4,000 machines in Vietnam. They "were employed in a different way. This is not to cast aspersions on their bravery or anything like that," he says.

Veterans

of 9 Squadron maintain to this day that with their relatively tiny force

they had to adopt different operational procedures from the Americans,

half of whose helicopter losses in Vietnam were in accidents.

Gration (right) recalls a night operation in the village of Dat Do in late 1969 when his patrol requested a medical evacuation. "We couldn't get the American dust-off choppers. We had a 9 Squadron helicopter that came and he stayed overhead for 20-25 minutes. I was a lieutenant-colonel at the time, trying to get him to land. But he wouldn't do it and eventually he went back to his base. He thought it was too insecure. That sort of thing does make an impression. I am sure a lot of Australian Army people who have served in Vietnam were aware that for most of our hot insertions into tactically dangerous situations and casevacs (casualty evacuations), we used the Americans."

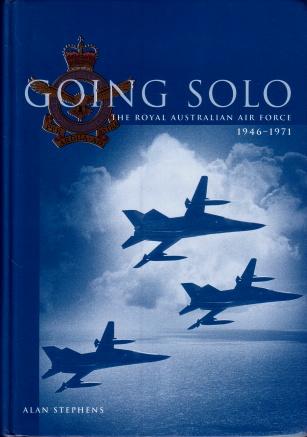

The fairest and most judicious account of the controversy comes from the RAAF's official historian Alan Stephens.

"While No.9 Squadron was to return to Australia after six years with the highest of reputations for its combat record, its experience during the first three months was an inter-service disaster," Stephens writes in "Going Solo: The Royal Australian Air Force 1946-1971", published in 1995.

Stephens notes that when 9 Squadron arrived in Vietnam in June 1966, just eight weeks before Long Tan, it was not prepared for war. Only two of its eight Iroquois were fitted with armoured seats, none had door gun mounts and the aircrew did not have chest protectors. The friction between the army and the air force over helicopter missions started right then, with the army quickly growing impatient with the RAAF. Soon after 9Squadron's arrival, Jackson even tried to dictate the composition of crew for some missions.

|

|

In the movies - When paying for a taxi, never look at your wallet as you take out a note, just grab one at random and hand it over, it will always be the exact fare.

|

|

"The most unfortunate aspect of the whole business was that from Long Tan onwards, No.9 Squadron provided the taskforce with exemplary support, unquestionably flying to higher standards and achieving better results than any comparable unit in the country," Stephens says. "Such was No.9 Squadron's skill, the SAS would not work with other (American) Iroquois units."

Scott says one of the main reasons why 9 Squadron was "not ready for war" was that the Defence Department had insisted the squadron would be given 10 years' notice before being sent into a conflict but, for Vietnam, it had only 12 weeks' notice.

By the end of the war, the squadron was widely regarded as the best Iroquois unit in Vietnam. Some American units came to Vung Tau to learn how the Australians managed to achieve such high mission availability from their helicopters, he says.

|

|

In the movies - Word processors never display a cursor on the screen, instead they will always say: "Enter Password Now."

|

|

Stephens has no doubt that the seeds of the 1986 decision to transfer the battlefield helicopters to the army were sown in the tumult of mid-1966, when Australians based at Nui Dat became used to hearing shouting matches between Jackson and Raw.

"As a consequence of the RAAF's perceived reluctance to provide the service they wanted, a group of army officers resolved eventually to gain control of the helicopters. It is questionable whether those officers understood either the full implications of their subsequent campaign or the proper use of air power, and an argument could be made that they were motivated primarily by prejudice and ignorance," he says.

In November 1986 the defence chief, General Phillip Bennett, supported by Gration, then army chief, and navy chief Vice-Admiral Michael Hudson, determined that the army should take over the battlefield helicopters.

At the time Gration argued that the army needed the authority to organise, train and equip battlefield helicopters in peacetime. The army argued that in operations the helicopters must be under full army control: they were not merely a transport vehicle but a combat arm.

Gration denies Long Tan was the catalyst for the change of ownership in 1986. "The central reason was by that time in sophisticated armies around the world, the helicopter had become a vital part of the tactical land battle," he tells The Australian.

"The helicopters were one of the elements of the manoeuvre land battle. That's the principal reason that we argued they ought to come to the army."

Some former air force chiefs and former flyers with 9 Squadron strongly disagree with Gration, arguing that the past two decades have proved the handover was not a sound strategic move. They argue the army has struggled to develop the flow of highly trained pilots, the technical know-how and the complex logistics and maintenance back-up needed to operate a new generation of battlefield helicopters, including the Tiger armed reconnaissance machines.

"I don't think the army (has) yet advanced to the stage where they are totally familiar with battlefield helicopters' operations," says former air force chief David Evans.

Evans,

who has written extensively on the subject, admits there is still

lingering rancour in the RAAF about the 1986 decision. "It was a very

foolish thing to do and it's proven to be that way since. We can't afford

to have

Present defence chief, Air Chief Marshal Angus Houston, a highly trained and decorated helicopter pilot, has no qualms about the army's ownership of battlefield helicopters.

In 1987-89, when he was the CO of 9 Squadron, Houston, in a masterly feat of inter-service diplomacy, oversaw the transfer of the helicopters to the army's Aviation Regiment. Houston told The Australian yesterday that there was no chance the decision would be revisited and praised the performance of the 5th Aviation Regiment Black Hawks in a string of complex operations during the past decade.

RAAF experts continue to argue that the combat effectiveness of the ADF has suffered from the decision taken way back in 1986.

They point to allied air forces such as Britain's, in which the battlefield helicopters are a combat arm jointly owned and operated by the Royal Air Force and the army, as a more appropriate model for Australia.

|

|

In the movies - The Eiffel Tower can be seen from any window in Paris.

|

|

|

|

NZ’s role

in Long Tan.

Gunfire at Long Tan: The Kiwi FO's StoryUntil March 1966 1RAR, 105 Bty RAA and my unit 161 Bty, RNZA were attached to the U.S. 173D Airborne Brigade at Bien Hoa. In May/June 1966 5RAR and 6RAR arrived in the theatre to establish the 1 Australian Task Force Area at NUI DAT in Phouc Tuy Province.

The motto, UBIQUE, used by a lot of artillery people, means “Wherever Honour and Glory May Lead”.As 161 Bty was to be in direct support of 6RAR, I was assigned as FO to D Coy from the time 6RAR assembled on the beach at Vung Tau. The sojourn on the beach ended when we occupied the base at Nui Dat. From then on my two radio operators and I, the three Kiwi gunners, shared the heat and mud with D Coy. We had D Coy laundry numbers and were involved in all of their activities.By August 1966 our party was virtually part of the establishment.

|

|

In the movies - You're very likely to survive any battle in any war unless you make the mistake of showing someone a picture of your sweetheart back home.

|

There came a time when neither Harry Smith nor I could perform our role while we were moving and, if we could not perform our functions, then the platoons would be in greater trouble. So it was decided to stop and establish some firm ground with one of the platoons. It was in that place where the wounded and members of the other platoons were gathered to establish a company defended area. My most intense recollections are of that final position.

Soon after initial contact, Harry Smith and I agreed on the grid reference

of our location and he requested fire support. Battery Fire Missions were

fired at some distance from the known position of 11 Platoon. Later, I

upgraded the fire to Regimental Fire Missions when the situation had

deteriorated and there were obviously large numbers of VC confronting us.

|

|

In the movies - If you need to reload your gun, you will always have sufficient ammunition, even if you hadn't been carrying any beforehand.

|

I have been asked how I was able to direct the fire. It was essential that I knew my location, and that I knew the direction of the platoons and roughly how far away they were. I tried to have my map oriented with the north point on the map facing north, then looked towards the noise of contact and small arm fire. That was the only way I had at that time of determining the grid reference at which to open fire. It was difficult to tell the distance the leading troops were from me, so the safety factor was that fire was opened some considerable distance, even up to 1,000 metres, away from where we were.Adjustments were made to move the gun fire closer. On one occasion I was told on the company net that it was too close. I actually screamed a number of times over the radio net the word "stop". This was because I could not hear many of the acknowledgements from the gun area when transmitting fire orders. Normally the artillery observers will give fire orders and will receive the acknowledgement. When I screamed "stop", the guns had to stop and they did. Another occasion when the guns had to stop and they were stopped for me, was when a helicopter was despatched to resupply small arms ammunition into the company area.

|

|

|

|

|

When the battlefield was cleared the next morning an eerie silence pervaded a scene of utmost devastation. The men may have been mentally and physically exhausted after their ordeal but they continued their duties at Long Tan until it was time to return to the Task Force base at Nui Dat.A Digger from D Coy later recalled:"It got to the stage where we all thought that there was no way we could get out of there. The only help we seemed to get was from the artillery. Every time the enemy troops got close to us it seemed that a salvo of artillery would land amongst them, just in time. We didn't have all that much ammunition anyway, and we were using our fire properly and not wasting it. When they did build up and move in quickly it was always the artillery that kept them out of our way."I am proud to have been with D Company 6RAR on that day.Maj M.D. (Morrie) Stanley , M.B.E.

|

|

In the movies - Once applied, lipstick will never rub off - even while scuba diving.

|

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

.jpg)

missions "became an instant part of army lore".

missions "became an instant part of army lore". In

all, 9 Squadron flew 237,424 missions in Vietnam between June 1966 and

November 1971. Through a combination of professionalism and good luck, the

squadron only suffered four combat deaths, the first of which occurred in

July 1970, fours years after the initial deployment. A total of seven

aircraft were lost.

In

all, 9 Squadron flew 237,424 missions in Vietnam between June 1966 and

November 1971. Through a combination of professionalism and good luck, the

squadron only suffered four combat deaths, the first of which occurred in

July 1970, fours years after the initial deployment. A total of seven

aircraft were lost.

Sergeant

Bob Buick took command of 11 Platoon after his platoon commander was

killed. When he requested artillery fire on his own position I spoke with

him directly on the company radio net. He had apparently assessed that

with about 10 men left out of 28, they could not survive more than another

10-15 minutes.

Sergeant

Bob Buick took command of 11 Platoon after his platoon commander was

killed. When he requested artillery fire on his own position I spoke with

him directly on the company radio net. He had apparently assessed that

with about 10 men left out of 28, they could not survive more than another

10-15 minutes.