|

Radschool Association Magazine - Vol 29 Page 10 |

|||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Print this page |

|||

|

|

|

||

|

MALAYA (1958 – 1961) Wilf Hardy

I was in the poo! I’d taken off early one Friday

afternoon, together with John Rice and Bob Hollingsworth in Bob’s Ford

Prefect, leaving a boring wait at Richmond before deployment to

Butterworth. Acting CO Flt. Lt. Fred Lindsay was giving me heaps after

sending a telegram to my parents’ home in Murwillumbah (I still have the

telegram) ordering me back for immediate onward movement to Malaya. Of

course being the only single

I was to eventually recognise Fred Lindsay as one of nature’s gentlemen and he was a great help to me later in Malaya when it seemed the whole world was against me. We named our second son Michael Lindsay - well, I didn’t want the poor kid called “Fred” all his life. I regret that Fred has now passed away, as it would have been nice to tell him of the positive influence he had on me all those years ago. A short stop-over in the Cockpit Hotel in Singapore, then by Malayan Airlines DC3 to Penang saw us picked up by RAF Police (Pommy Red-Caps) in a Land Rover for the trip via the old side-loading Penang-Butterworth ferry to the air base. I’ll never forget my first whiff of the tantalizing “smell of the East”, which I guess is and always has been mainly garlic and raw sewage.

After settling in, a group of Plotters and one LAC Rad Tech ‘G’ (still evidently under Fred Lindsay’s punishment) was sent up north by RAF 60 foot launch to Song-Song bombing Range to triangulate Canberra released bombs splashing into the sea (hopefully) near a tethered target. We lived in a dorm hut on the idyllic tropical Song-Song Island, dining on etherized eggs, reconstituted powdered spud and dehydrated spinach together with bangers and whatever fish we could catch. The standard drink was a concoction tasting vaguely like orange cordial made from powder contained in packets invariably bearing a manufactured date of 1941.

The OC was an RAF Flt. Lt. Canberra navigator who spent much of his time perfecting his quick-draw with the RAF issue.38 revolver, getting “ready” for his trip up from Singapore on the 24 hour train trip to Prai - he was the only one of us with a firearm. I remember being dropped off for a lonely day on Telor Island (which means egg) and the description fitted well. At high tide a strip of sand barely a meter wide met almost vertical and impenetrable jungle rising to the top of the island’s solitary hill. Another chap was dropped off miles away at another island the name of which escapes me, but it meant “pregnant woman” and it sure looked like a pregnant woman lying flat on her back.

The launch came in as close to the beach as possible and I had to jump into six feet of water and wade ashore trying to keep my lunch dry holding it over my head. At one end of the strip of sand was a crude hut mounted on four rough-hewn timber poles about 20 feet high and accessible via an equally crude ladder. Inside the hut was a rudimentary sight and quadrant to enable a bearing to be taken of the bomb splashes and some sort of RAF aircraft radio, powered by a battery. All pretty straight forward, just listen out for the Canberra on its bombing run then take a bearing of the splash and record it. Except the radio didn’t work and my one effort at being a Plotter was a dismal failure.

I only saw three splashes all day and as my Penang

‘copy-watch’ with the bamboo hairspring had stopped, I couldn’t even

record the time of the splashes I did see! However the thing that had

given me cause for alarm

These giant reptiles have saliva so corrosive it will melt flesh, so I was glad they couldn’t climb ladders and I started to wonder why the hell I was left there unarmed, which was the start of my experiences in Malaya with no means of defending myself. There were still Communist Terrorists (CTs) in the Penang area. 38 CTs were known to be operating in the jungle on Penang Island. Efforts by us young “bullet proof” fellows to tempt fate by driving around the island late at night on that weirdly cambered twisty road were often thwarted by police and Ghurkha sweeps attempting to round up the CTs.

|

|||

|

This really does work !

I've tried it several times and it worked every time - even tried it again this morning! If you feel like doing some work, sit down and wait…..The feeling does go away.... |

|||

|

Amnesty leaflets littered the outer suburbs of Georgetown, dropped by RAF aircraft and now 50 years on, I regret not collecting at least one to keep for posterity. An RAF Dakota fitted with a powerful audio amplifier and banks of huge speakers under the fuselage often droned over the jungle calling in Chinese for the CTs to surrender. I’ve learned in recent years that the Secretary General of the Malayan Communist Party, one Chin Peng, managed to spirit most of the Penang CTs out to Singapore disguised as students, whilst others were smuggled across to Sumatra by bribing fishermen. (See Alias Chin Peng - My Side of History (2003), ISBN 981 04 8693 6).

However, what Chin Peng didn’t admit in his book, was that in ‘59 one starving CT staggered out of the jungle with a rusty .303 and surrendered to a group of Army wives on the Minden Barracks golf course! The ladies took him to the Officers Mess and fed him a sandwich, whilst they awaited the arrival of the police to arrest him.

However it wasn’t always amusing. Also in ‘59 there was a gunfight between the police and a senior Communist cadre in the cave temples just outside Taiping south of Butterworth, when the CT was shot dead. I well recall the CRUMP of exploding bombs dropped by the Canberras west of Butterworth when the squadron eventually began operations, easily heard outside the unit shelters. Throughout my two and a half years at Butterworth the only firearms I handled were drill .303s as it seemed I was just the right height to catch all the ceremonial crap. There was an exercise in ‘60 when the Techs were given Mk 1 Sten-guns (mine had a broken stock) which had been made during WW2 for two shillings and sixpence each – and they looked like it too! I never once went onto a rifle range in Malaya and from memory probably did more range time as a 14 year old ATC cadet than in my whole six years in the RAAF.

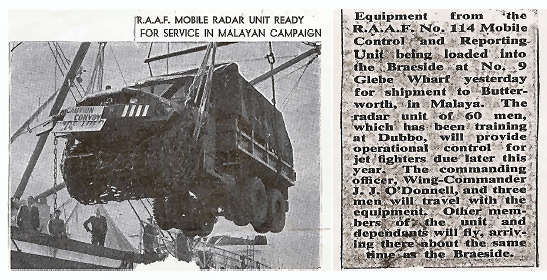

The advance party had been at Butterworth about a month when the SS Braeside arrived off Prai carrying the unit radar equipment. There were a few unit personnel accompanying the gear on the ship, including the CO, Wg. Cmdr. “Butch” O’Donnell, whose nick-name was totally the reverse of his gentle nature. On parades, he could never get the hang of it all and seemed to have two left feet! In those days, all cargo was off-loaded onto lighters out in the shipping roads using the ship’s derricks, then the lighter was towed to the Prai wharves, where the cargo was craned ashore. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

The task of guard duty for the steadily increasing line of fifty M35 trucks and trailers containing our radar equipment on the wharves fell to the advance party. Perhaps I was still being punished by Fred Lindsay, but I always copped the midnight to dawn shift. It was always the same; I’d be driven the 20 odd miles south of Butterworth to the Prai wharves by the Pommy Red Caps in their Land Rover and left on my own. I recall the first time, the shocked Red Caps asking Sdn. Ldr. Jeff Swensen why the hell I was being left down there unarmed and even the suggestion that we should have at least a night-stick was turned down.

One night about 3.00am, a hell of a hullaballoo arose and hundreds of Malays from the local Kampong came rushing along the wharf. I tried to stop one elderly chap to ask what the commotion was all about. We’d been equipped with a RAAF produced English/Malay dictionary of sorts before leaving Australia, which I recall had been printed in early 1942. It contained such helpful phrase for 1958 like; “Many Japanese aircraft are coming”......................All I could get out of him was a shouted “TIGER, TIGER”! as he rushed by. You could say: “Shits Were Trumps”! There I was on that deserted wharf at 20 years of age, on my own, 20 miles south of Butterworth, unarmed (apart from my thermos filled with that vile tasting orange cordial made in 1941), no telephone, no radio and without any transport!

A photo I’d seen in the Straits Times of a tiger shot by Kampong Malays, showed an animal measuring 12 feet from the tip of its nose to the tip of its tail - the Sumatran Tiger was a damn big cat! If the thing came slinking along the wharf, I considered jumping into the water, but one look at the flotsam, oil, dead dogs, raw sewage (and probably discarded garlic) discouraged that avenue of escape. Besides which, I knew that unlike a tabby cat, tigers could swim. So I climbed into the cab of an M35 (with its canvas hood), hoping the oily smells of the vehicle would mask my scent, wound the windows up and stayed there for the rest of my shift. |

|||

|

What other people think of you is none of your business.

|

|||

|

|

|

||

|

What the hell were our Lords and Masters thinking, to

place us in Harm’s Way without any method of defending ourselves? Years

later, working for Navy, I used to watch sailors who were no older than we

had been in Malay in 1958, training to board illegal vessels in our North,

armed to the teeth with 9mm pistols, SLRs and Owen guns. Why were we never

armed in Malaya? Even the fellows who guarded the radar equipment prior to

loading onto the SS Braeside in Sydney had been issued with a .303 and

bayonet - we had nothing! The argument had always been that if we had

encountered any CTs, they would have taken the rifle off us; never

The advance party turned out to greet the rest of 114 MCRU personnel when they arrived by chartered QANTAS Constellation toward the end of August. Married members and families were bussed to the Australian Army Hostel on Penang Isl and where they were billeted until allocated houses, generally in the better northern area of the Island. Assembly of the unit equipment then proceeded in earnest. The site had been pre-prepared at the south-western end of the old wartime runway and consisted of permanent buildings for stores, amenities, offices and fitters’ workshop. The search radar and height finder antennas were installed on two mounds, whilst demountable buildings which were part of the equipment package were erected and consisted of operations shelter, search and height finder shelters and diesel generator shelter.

In addition, self contained cabins and antennas for VHF receivers were adjacent, with the VHF transmitters on the north-western end of the runway. Cabling was supported 18 inches above ground, which proved a problem as the locals employed to cut the grass with a small scythe swung in a continuous circular motion resulted in many cut cables over the years. The VHF transmitter site was a haven for snakes and on one occasion I alighted from my jeep and strolled across the gravel hardstand daydreaming, through literally hundreds of sunbaking highly venomous vipers without noticing them or even stepping on any of them.

After the shock of seeing them, I was reminded of Tiny Tim singing “Tiptoe Through The Tulips” trying to regain the jeep without being bitten! |

|||

|

|

|||

|

114 MCRU, c. 1960. RAF HF comms vans were provided, on loan, as a backup, in the event of lost landlines to Singapore. |

|||

|

It was imperative that the radar be up and running for the arrival of the first flight of Sabres, air ferried from Australia via Biak and Labuan and scheduled for end of November and I don’t recall any real problems in achieving this date. The refuelling stop at Biak off the north coast of West New Guinea was touch and go as the Dutch East Indies was in its dying last days, with only a handful of Dutch nationals on hand to receive the Sabres. The real concern however was the long flight from Labuan across the South China Sea, the Malay Peninsula and into Butterworth as an aircraft going down into the jungle was to remain a daily concern throughout the years.

|

|||

|

Time heals almost everything. Always give time time.

|

|||

|

However there was a sigh of relief when the nose paints of the Sabres came up solid as the aircraft popped up over the horizon at a range of 215 miles. I’ve always been fascinated at the fanatical secrecy surrounding the maximum range of those radar sets at that time. For centimetric radar of high transmitter power and state of the art, but noisy, valved receivers, given no obstructions and with the type of air craft available at that time, range had to be a function of the height of the aircraft and curvature of the earth. Of course we had obstructions, obviously relating to the radar site being just above sea level and these were to the west due to Penang Island and to the north-east due to Kedah Peak. However remaining bearings were not too bad as evidenced by successful air defence exercises. This was provided the “enemy” didn’t cheat, although I recall one time the RAF sent in a few Beaufighters at coconut palm height, when the air traffic controllers were the first to see them; through binoculars!

However, in the air defence sense, the problem of the day was a high flying bomber at just under Mach 1 carrying an atomic weapon. The fighters were not much faster than the average bomber and attacking at, or very near, Mach 1 gave the bomber a distinct advantage. If the enemy got within 20 miles, then it was considered we’d lost, and as the Sabre took 6 minutes to reach 40,000 feet which was pretty near its service ceiling, there was generally only time for one pass to down the bomber. |

|||

|

No matter how good or how bad a situation is, rest assured, it will change.

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

I recall one time a Russian aircraft was heading our way some 140 miles off track and due to so many squadron bods taking “leave in lieu” for guard duties etc, not one Sabre out of 38 was serviceable and RN aircraft out of Kuala Lumpur were scrambled. The RAF Vee Bombers used to wait until the Sabres closed on them, then stand on their tails and go straight up, leaving the Sabres wallowing below. However the main task of the unit was vectoring the Sabres and Canberras to strikes at CT targets designated by ground forces and this task stayed with us on a regular basis throughout my time. I recall some unserviceabilities which worryingly delayed strikes and then it was a rush to get the gear working again. I worked mainly the search radar, which in hindsight was pretty reliable. We invariably lost a magnetron occasionally, but it was the front end of the receivers which were usually the problem, with poor receiver performance and although I worked on literally hundreds of radar systems of all types both military and commercial after I left the air force, I never again struck a system which had so many failed mixer crystals.

|

|||

|

|

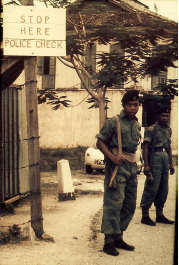

Malayan Police at the checkpoint to a village north of Kuala Lumpur 1958. They were armed with Mk5 Enfield .303 Jungle Carbines.

That’s my Berkley B65 sports car in the background.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

The radar used radioactive pre-TRcells which used to burn up with gay abandon. The approved disposal method for these radioactive materials, was to bury them at least 2 feet underground and place a “foul ground” sign over them; the graveyard was just to the south of the search radar mound.

I’ve often wondered what happened to this dangerous site; I assume the Malaysians are now growing vegetables there!

Another task for our aircraft was the bombing of any cultivation sighted in the jungle as part of the CT food denial program. The CTs mainly relied on food being spirited to them by Chinese squatter sympathisers on the fringe of the jungle. To prevent the smuggling of rice, the larger villages used central cooking, where all rice was cooked in policed kitchens and as the rubber tappers went onto the estates, they were only given cooked rice to carry, which was largely useless to the CTs as it became rancid and inedible after several hours.

The smaller kampongs were surrounded by barbed wire and police searched travellers both entering and leaving the village. Many of these measures were seen as we drove about the countryside on leave, as we were also subjected to these restrictions. If any locals were caught smuggling food, they were charged before a Magistrate, invariably found guilty and hanged. That sort of discouraged them a bit from doing it.

|

|||

|

|

Me, at the entrance to the first declared CT free (White Area) north of Kuala Lumpur – in 1958.

|

||

|

|

|||

|

Being unarmed still irked us and a number of us tried unsuccessfully to obtain pistol licences from the police in Georgetown. You could buy firearms from many outlets and just about every European civvy on the mainland carried a pistol. Once I drove up to Kroh on the Thai border, which was still very much a “black” area (“white” areas were those designated CT free) where I was taken to task by the Malay border police and told to clear out as a policeman had just been shot by the CTs. On another occasion I entered a hill climb event in Ipoh in my Berkley B65 mini sports car and what a peculiar sight; the road was protected for the full ength by armed police just in case the CT s decided to join in the motor sport event!

|

|||

|

An elderly gent was invited to an old friend's home for dinner one evening. He was impressed by the way his buddy preceded every request to his wife with endearing terms such as: Darling, Honey, My Love, Pumpkin, Sweetheart, etc.. The couple had been married almost 70 years and, clearly, they were still very much in love. While the wife was in the kitchen, the man leaned over to his host, and said: "I think it's wonderful that, after all these years, you still call your wife those loving pet names." The old man hung his head. "I have to tell you the truth," he said. "Her name slipped my mind about 10 years ago, -- and I'm scared to death to ask the old girl what it is."

|

|||

|

A most important function of the unit was tracking aircraft to pinpoint locations of crashes. The forests of the Malayan jungles contain some of the highest and fastest growing trees in the world, commonly reaching 300 feet in height. If you take a tour around the Botanical Gardens on Penang Island today, you will see examples of these incredibly tall, straight trees, totally devoid of branches for the first 150 feet or so and growing to a height of 300 feet in as little as 80 years! The RAF had lost pilots in the southern states of Malaya due to parachutes being snared in the tops of these jungle giants, leaving the pilot with the choice of starving to death or dying in a fall to the jungle floor.

Very early, our pilots’ parachute harnesses were provided with a long length of cord to give some hope of getting down out of a tree. It was therefore imperative that we identify the locations of lost aircraft as quickly as possible. On one occasion, a British Army Auster was lost on the 50 mile flight from Butterworth to Taiping; nothing was ever found of the aircraft or pilot even though we had the coordinates. On another occasion, during practice intercept training, two Sabres collided. The “collidor” made it back to Butterworth, whilst the “collidee” broke up, with the pilot ejecting and alighting on the side of a hill from where a rescue helicopter was unable to carry out a retrieval. And yes, the downed pilot was un-armed, so a pistol had to be dropped to him together with rations to await the RAF Malay Squadron (our airfield defence unit) walked in to get him. (The cooks in our mess packed the food for him and included a cold tinny of VB)

|

|||

|

Growing old beats sure the alternative every time -- dying young.

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

Me, (left), with Brian James at Labuan Island, April 1959.

|

||

|

|

|||

|

Types of aircraft in Malaya at the time included; RAF Hastings (a 4 engine transport with a tail-wheel, bit like a DC3 on steroids), Valetta (twin radial light transport, bit like a normal, DC-3), RNZAF Bristol Freighters (invariably called “Frighteners”, these terrible aircraft operated a shuttle service between Butterworth and Changi which was known as the BUT-P. If it rained in flight, a river ran through the aircraft where the water came in through the ill-fitting clamshell doors at the nose). RAF Beverley (a giant cargo/troop carrier with fixed undercarriage), Dakotas, Westland WS-55 helicopters, RAF Javelins (a twin jet night fighter which looked fabulous with its delta shape, but was a real dog), the three types of RAF Vee Bomber, which turned up from time to time on tropical trials (the nose-wheel collapsed on a Valiant, pinning some poor fellow’s leg under the fuselage), Beaufighter, Canberra; both ours and RAF and of course our Sabres.

We occasionally also saw RN and RAN carrier aircraft. Then there were heaps of British Army Austers with big balloon tyres and our A model Hercules turned up in 1959.

Other memories were of the Brit’s making, like trying to open a cheque account at the fine old British Chartered Bank and being told only military personnel over the rank of Warrant Officer could open a cheque account (I went and opened an account at the Hong Kong Shanghai Bank over the road). Once, an RAF sergeant called me a “colonial” and I was probably lucky not to be charged with insubordination when I laughed in his face. I remember being turned away from the Selangor Cricket Club in Kuala Lumpur (it was called the Spotted Dog as it was painted in red and white stripes) because I wasn’t an officer.

I stayed a night at the Coliseum Hotel in K.L. which was like a wild-west bar; rubber planters came to town in their V8 Mercuries armour plated with steel cut off old Jap tanks and checked their guns at reception before entering the bar. Then later at night, well and truly under the weather, retrieved their guns and charged back to their estates hoping they wouldn’t beambushed by CTs.

|

|||

|

If we all threw our problems in a pile and had a chance to see everyone else's, we'd all grab our own back.

|

|||

|

The Malayan Emergency was declared over on 31st July1960. And that was the end of the British General Service Medal (Malaya) which was the requirement to get a war service home loan. There was a grand parade in Kuala Lumpur, but it all seemed to go off with a whimper in Penang, although I still have a photo of a banner across Penang Road declaring “Victory Over Communism”. There was a tower built near the Butterworth main gate, manned by Ghurkhas with a bren-gun. Somewhat cynically, we thought it was built for a photo shoot on the great day, but realistically it was probably built in case the TCs decided to stage an attack to spoil the party.

|

|||

|

|

Penang Road, 31st. July 1960 - the supposed end of the Malayan Emergency.

|

||

|

|

|||

|

But it didn’t end then at all. The Secretary General of the Malayan Communist Party, Chin Peng, moved from southern Thailand to China and in the mid ‘60s, Chairman Mao ordered him to get back to Malaya and take it and China armed him properly to do so this time. So there was a second Emer gency which lasted until 1989, with most of the fighting on the Thai border. Amazingly, Chin Peng, now in his late 80s, still lives in southern Thailand and has caused an uproar lately trying to get back into Malaysia legally! The Malaysian government won’t have a bar of it.

Most of the unit’s first deployment personnel returned to Australia by chartered ship (which caught fire in the Mediterranean some years later and sunk!) in December 1960, although some came home in small cargo vessels carrying a handful of passengers and taking a month to get back by way of meandering through SE Asian ports. This was an old Pommy idea of unwinding after the rigors of the East, a sort of slow boat to/from China. I had been asked to stay on a couple of months as the penny had finally dropped and disclosed that many of the Techs in the second deployment had not been trained on the equipment. I finally left Butterworth on 1st February 1961 having been close to first of our group in, and definitely last out.

However, with a bit of help from me, Helen had gone and

got herself pregnant, so we had to fly home first class on a

I became involved in Navy Air with GCA, Airfield Surveillance, aircraft ASW equipment and extensively, with all types of airfield navaids and facilities. In 1968 I had a final contact with air force radar. I was working on the air craft carrier HMAS Melbourne, which had a Dutch Philips air search radar which used a 5J26 magnetron, the same as I recalled in the FPS3 installed at Brookvale and MPS7 at Butterworth. The magnetron current was excessively high and power output very low and for the first and only time in my long experience I found the magnet had somehow lost its field strength. As navy did not have a spare, I was able to get approval through navy and air offices in Canberra to obtain an air force spare and drove over to Brookvale and picked it up. So a part of 1CARU Brookvale carried on giving service long after Brookvale was closed down, until the old flagship was broken up in a Chinese shipyard in the late‘80s.

Eventually I moved into Navy Air project management for everything from air nav aids, to buildings and even a sewage treatment plant, rising to STO3 in the public service. Some of my projects were single service managed by air force and it was at that stage of my career that I began to cross paths with bods from my air force days, one being my old sergeant Arthur Ellem, who was a Wing Co at that time. I retired in 1993, moving to Townsville to escape what had become a most stressful occupation and Helen and I have enjoyed a wonderfully peaceful retirement in North Queensland these past years.

Throughout my career in radar, radio and project management, I’ve been very mindful that it all started at RSTT Wagga and 7 Rad Tech G course at RADSCHOOL Ballarat, then began to blossom in Malaya, 1958-1961.

|

|||

|

Don't take yourself too seriously. No one else does.

|

|||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward

|

|||

member of the absconding group, it was all my fault and for punishment, I

was to be sent up with an advance party of Plotters - Boy, Oh Boy - some

punishment! I know the date we flew out of Mascot in a Qantas Super G

Constellation (wearing civvies in case we had to land in politicly

unstable Indonesia due to an unserviceability) as I still have the carbon

of my airline ticket – 25th. July 1958.

member of the absconding group, it was all my fault and for punishment, I

was to be sent up with an advance party of Plotters - Boy, Oh Boy - some

punishment! I know the date we flew out of Mascot in a Qantas Super G

Constellation (wearing civvies in case we had to land in politicly

unstable Indonesia due to an unserviceability) as I still have the carbon

of my airline ticket – 25th. July 1958.  and effectively kept me in the hut all day, were the slither and huge claw

marks in the sand. I guessed they couldn’t be Goanna tracks and after

being picked up late that afternoon by the launch, later, I was told there

was a colony of Komodo Dragons on Telor Island!

and effectively kept me in the hut all day, were the slither and huge claw

marks in the sand. I guessed they couldn’t be Goanna tracks and after

being picked up late that afternoon by the launch, later, I was told there

was a colony of Komodo Dragons on Telor Island!

mind

that they would have shot us anyway. Just prior to our arrival in Malaya,

a British Army vehicle recovery team had driven out to a broken down truck

in the southern state of Johore, the sergeant in charge taking his 15 year

old son with them for an outing. They were ambushed and all shot dead by

the CTs, apart from the 15 year old. I think at about this time I started

to realise it wasn’t like The Adventures of Biggles after all and perhaps

I’d joined the Air Farce!

mind

that they would have shot us anyway. Just prior to our arrival in Malaya,

a British Army vehicle recovery team had driven out to a broken down truck

in the southern state of Johore, the sergeant in charge taking his 15 year

old son with them for an outing. They were ambushed and all shot dead by

the CTs, apart from the 15 year old. I think at about this time I started

to realise it wasn’t like The Adventures of Biggles after all and perhaps

I’d joined the Air Farce!.jpg)

QANTAS

707 instead of taking that slow boat to/from China. I’ve often wondered if

there were others from my time in the service who used their radar

experience as effectively as I did on discharge. I’d been doing some work

on ships’ radar in Penang and carried on from there with AWA, who at the

time were agents for every make of marine radar in the world, except

Decca. So I covered Sydney, Botany Bay, Newcastle and Port Kembla at a

time when there were many small and large vessels operating along the

coast, servicing dozens of radar sets. I then moved to Navy at Garden

Island where over another 10 years I could total experience on well over a

hundred radars. On top of this there were overseas and local courses and

overhaul, installation and repair of missile guidance, air search,

gunnery, CCA (aircraft carrier precision approach) systems, comms from MF

to UHF, ECM, ECCM on HMA ships and systems so diverse I could never keep

track of them.

QANTAS

707 instead of taking that slow boat to/from China. I’ve often wondered if

there were others from my time in the service who used their radar

experience as effectively as I did on discharge. I’d been doing some work

on ships’ radar in Penang and carried on from there with AWA, who at the

time were agents for every make of marine radar in the world, except

Decca. So I covered Sydney, Botany Bay, Newcastle and Port Kembla at a

time when there were many small and large vessels operating along the

coast, servicing dozens of radar sets. I then moved to Navy at Garden

Island where over another 10 years I could total experience on well over a

hundred radars. On top of this there were overseas and local courses and

overhaul, installation and repair of missile guidance, air search,

gunnery, CCA (aircraft carrier precision approach) systems, comms from MF

to UHF, ECM, ECCM on HMA ships and systems so diverse I could never keep

track of them.