|

Radschool Association Magazine - Vol 32 Page 7 |

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links | Print this page |

|

My Story! |

|

|

|

Gareth ‘Gary’ Kimberley[1]

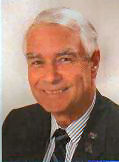

Gary Kimberley was born in Fremantle, Western Australia, in 1936.

As a teenager his interest in aircraft led him to join the Air Training Corps as a cadet and in 1955, at the age of 19, he began flying lessons on Tiger Moths at Maylands in Perth. In 1956 he gained his private pilot’s license as a result of being selected for aircrew training during National Service in the RAAF.

He joined the RAAF as a pilot in 1960, on No 40 Pilot’s Course, training on Winjeels at Point Cook and finally gaining his wings on Vampires at Pearce. He then went on to serve in a number of different RAAF units including the Air Trials Unit on the Woomera Rocket Range followed by a two year posting to No 10 Squadron at Townsville flying Neptune long range maritime patrol aircraft.

In 1965 he

transferred to No 38 Squadron at Richmond to fly the Caribou and

completed a nine month tour of active service in Vietnam in 1965 - 66.

During his time in the war zone he flew 1,109 operational sorties

totalling 742 flying hours with his aircraft often fired at and actually

hit by enemy ground fire on several occasions. Fortunately the aircraft

was not seriously damaged. He also flew extensively throughout Papua

He joined Qantas International in 1970 to fly Boeing 707s and 747s and subsequently enjoyed numerous overseas short term postings with that airline. In 1978 he designed and built his own ultra light aircraft, the Kimberley Sky-Rider (a single seat, wire braced high-wing monoplane with aluminum tubing fuselage and single surface Dacron sailcloth wing. 12 hp McCulloch engine. Cruise at 40 mph and stalls at 23 mph. Wing span 32’4”. Wing area 144 sq/ft. Length 18’, height 7’ 10”. Empty weight 210 lbs.) for which he received an outstanding individual achievement award from the Experimental Aircraft Association of the United States. The Sky-Rider was featured in the 1981 – 82 edition of the “Aviation Bible: Jane’s All The World’s Aircraft (Jane’s, p. 606). (The photo above is a Powered Quicksilver)

In 1996, completing a flying career spanning more than forty years, Gareth finally retired from flying as a Qantas Boeing 747 First Officer. He had logged a total of 17,600 flying hours on more than 30 different aircraft types ranging from Air Force jets (Vampires, Meteors and Macchis) to four engine Qantas Jumbos.

He has contributed short stories and anecdotes to several books on the Vietnam War and had a book published in the United States on how to build and fly ultra light aircraft. He also served briefly as the ultra light aircraft correspondent for the Australian Flying magazine and had numerous articles published in Australian and overseas aviation magazines.

In 1998 he ran unsuccessfully as a candidate for the Australian House of Representatives. For several years, spanning 2001-2002, he published the political newsletter Fact File and still writes a non-partisan political column for several national monthly publications.

He now lives in Sydney with his wife Patricia and has two married daughters.

Following are some stories of his more memorable moments while flying with the RAAF.

Vietnam

"I was posted down to 38 Squadron at Richmond because I was assured of obtaining a captaincy on Caribous quickly. I knew I would have to go to Vietnam but the thought of spending another two years as a copilot on Neptunes at 10 Sqn. did not appeal to me. My girl friend, Patricia, followed me down to Richmond and we decided to get married. Fortunately, we were able to the RAAF chapel on the base for our wedding ceremony – that was 23rd October, 1965.

My crew captain from 10 Sqn, Flying Officer Bob Maggs, had insisted on being Best Man and he and my buddy Flg Off Paul Smith had come down from Townsville for the big occasion.

As we came out of the chapel we were surprised and delighted to find that four of my friends Daryl SuIlivan, Kevin Henderson, John Stahl and Don Pollock, in full dress uniform, had formed an archway complete with ceremonial swords held high.

With my departure date for Vietnam now set for mid November, we didn’t have much time. My Caribou conversion concluded with a trip to Hobart on the 1st November. The trip down was via Melbourne with an overnight stay at Wrest Point hotel in Hobart (The RAAF always do it tough) and return the next day was via Laverton. I had finally made the grade. I was now a fully fledged Caribou Captain, and incredibly, it had all been achieved in less than 4 months.

The few weeks prior to my departure were quite depressing with anti-war demonstrations starting and songs on the hit parade such as The Eve of Destruction, Blowing in the Wind, The Times they are a-changing and I ain’t marching anymore, all promoting an atmosphere of doom and gloom and rebellion. Initially, tours of duty in the war zone were eight months but I ended up extending for a month to facilitate meeting up with Pat in Singapore for the start of our much delayed honeymoon. In 1966, the tours were increased to 12 months, but nine months was plenty long enough for me. |

|

|

Flying the airplane is more important than radioing your plight to a person on the ground incapable

of understanding or doing anything about it.

|

|

Unlike the American :and Canadian Caribous, which had autopilots filled as standard, the Australian Government decided that as the aircraft would only be flying very short sectors, it could save money by buying the aircraft without the automatic pilots. As anyone who spent any time at 38 Sqn knows, we subsequently flew Richmond to Perth, Richmond to Darwin, Richmond to Townsville, Hobart and to Port Moresby, transcontinental distances and having to fly the aircraft by hand all the way. Smart thinking Mr Dept Air.

A lot of the US Caribous also had weather radar while we were limited to the Mark I eyeball. I suppose there were several advantages however, without the weight of the autopilots and radar we could carry a (tiny) bit more payload and, of course, there was a commensurate reduction in spares carried (and it made the Radtech’s job that little bit easier - tb)

On the 13th November 1965, I met up with my travelling companion, FIt Lt Noel Bellamy, at Mascot airport, and boarded the Qantas Boeing 707 for Vung Tau.

There I kissed my bride of three weeks goodbye and boarded the Qantas Boeing 707 on the first stage of my journey to the war zone.

Qantas didn’t fly to Vietnam so we could only go as far as Singapore with our national carrier. At Singapore we would have to stay overnight and catch the daily Pan American Airways flight to Saigon the next day.

For me the flight to Singapore in the Qantas Boeing 707 was quite exciting for although it was 1965 and I was relatively old at 29, it was the first time I had flown in a large 4-engined jet airliner. After the roaring, rattling Caribou the quietness, smoothness and air conditioned comfort of the 707 was quite a contrast. This was clearly a most civilised way to fly.

Singapore was a busy, exciting place. It had just seceded from Malaysia under its new Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew and was still celebrating its independence. British rule had previously kept the various racial groups under control but with post war independence, the predominantly Chinese Singapore had objected to being governed by Malays in Kuala Lumpur and had opted for secession.

On November 14, 1965, Flt Lt Noel Bellamy and I boarded our Pan Am Boeing 707 and were flown the relatively short distance from Singapore to Saigon. We landed at Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut airport to the news that two Australian Army advisers had been killed in action at Tra Bong the previous day. Warrant Officers Wheatley and Swanton had gone out with a company of Vietnamese troops on a search and destroy patrol when they were engaged by a company of Viet Cong and Swanton was badly wounded. Wheatley courageously stayed behind in a desperate attempt to carry his wounded comrade to safety but they were quickly overrun by the Viet Cong and both men were shot and killed. Kevin “Dasher” Wheatley was subsequently awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross, but hearing of the deaths of Wheatley and Swanton did nothing to boost my morale. |

|

|

|

|

Flashlights are tubular metal containers kept in a flight bag for the purpose of storing dead batteries.

|

|

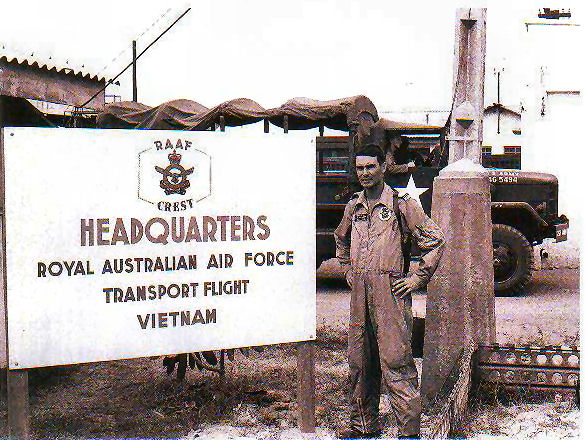

Tan Son Nhut airport was more than a hive of activity, it was absolute bedlam with aircraft, men and machines flying everywhere. It was like nothing I had ever seen before. We were dumped on the tarmac and simply told to report to the United States Air Force movement control centre, which we did. There we were told that a “Wallaby” Caribou would pick us up and take us to Vung Tau, the US Army airfield where the Australian Caribous were based.

After waiting several hours in sweltering heat our RAAF Wallaby eventually arrived and parked out on the vast apron in amongst Boeing 707’s, C-130 Hercules, C-141 Starlifters, giant Globemasters and a plethora of other aircraft which made our little Caribou really look quite insignificant. I had never seen so many aircraft in one place in my whole life. Indeed, at that time Tan Son Nhut was reputedly the busiest airport in the world. We were met by the Wallaby crew and welcomed to South Vietnam. We threw our gear, which in my case consisted of my Air Force issue large steel trunk, a standard suitcase and an overnight bag, into the Caribou and were flown quite unceremoniously across to Vung Tau on the coast – an action-packed 20 minute flight. We were welcomed at RTFV Headquarters on the base by our CO, Sqn Ldr Doug Harvey and then taken by Jeep into town to the ‘Villa Anna’, a lovely old French villa by the sea where the RTFV officers were billeted.

Ironically, despite the dangers of operating in the war zone in South Vietnam, we actually lost more aircraft and suffered more casualties operating in Papua New Guinea than we did in Vietnam. The reasons for this were Inaccurate PNG maps, shocking weather, a lack of radio navigational aids, poor communications, mountainous terrain, and some of the most difficult airstrips I have ever had to get into and out of. I had more frightening experiences flying in PNG than I did in Vietnam. (From experience, I would say a contributing factor would also be “Pilots who knew everything and wouldn’t or couldn’t be told” – tb).

There were some airstrips the American Caribous would not go into, Plei Me being a notable example. As a result the RAAF Wallaby was the only decent sized aircraft that operated into these isolated camps. In 1966 the United States Air Force took over the US Army Caribous which for a while even further restricted American Caribou operations.

Apart from the weather and the topography, the two main hazards to flying in South Vietnam were the risk of a mid-air collision because of the sheer volume of air traffic over the country at the time and the ever present danger of being hit by enemy ground fire. The Caribou tactical transport aircraft operated by the RAAF Transport Flight, Vietnam (which quickly grew to become No 35 Squadron) were large and slow moving targets.

Our answer to the ground fire problem was to avoid flying below 2,500 feet wherever reasonably possible. We figured that the chances of being hit by small arms fire above this height were minimal and experience seemed to bear this out. Heavier, 50 calibre weapons of course were another matter.

We would fly to our destination at a safe height, then when directly over the top, descend in a steep spiral, attempting to remain within the range of the camp’s defensive fire. We would leave the same way, climbing up to a safe height directly above the camp before setting course for the next strip. This technique was usually successful, but not always, and every now and again we’d pick up the odd round or two. At that time, we had not had a single passenger or crew member killed or even seriously injured. In fact, the RAAF Wallabies had an excellent reputation for safety and reliability, and none of us wanted to spoil it.

Tours of duty in Vietnam were eight months and RTFV, as it was when I arrived, although operating in support of the USAF’s 315th Air Commando Group, was based with an American Army Caribou squadron at Vung Tau, 38 nautical miles south-east of Saigon.

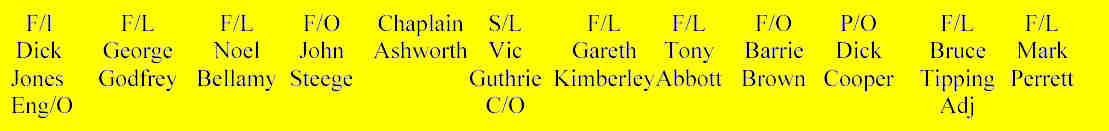

The CO of the Flight when I arrived was Sqn Ldr Doug Harvey. He was replaced in November by Sqn Ldr Vic Guthrie who in turn was replaced by Wg Cdr Charles Melchert in June 1966 when the Flight became No. 35 Squadron. In addition to our two semi-permanent detachments at Nha Trang and Da Nang and the many and varied ad hoc missions we flew, we also operated a number of “bus runs,” the two main ones being the 405 mission to the north as far as Nha Trang and the 406 mission around the south of the country which was basically around the Mekong Delta. Both these scheduled services started and terminated at Tan Son Nhut. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Airspeed, altitude and brains. Two are always needed to successfully complete a flight.

|

|

Our radio call-sign was “Wallaby” followed by the last two digits of the Mission Number and on these daily bus runs we gained such a good reputation for punctuality and dependability that the Americans christened us “Wallaby Airlines”. So good was our reputation that I know for a fact some US Army personnel preferred to fly with us rather than in their own Caribous.

One of my first big missions proved to be quite exciting and turned out to be a pretty good introduction to the type of flying I could look forward to. It was December 16 and I was programmed for a 41 Mission in A4-191 with my old course mate Graeme Nicholson who, like me, held the rank of Flying Officer. Our day’s work was to fly various cargoes to the numerous airstrips in the area to the north of Saigon and Vung Tau.

The first call was to a Special Forces camp which was listed as An Loc and having found what we thought was the correct strip we duly landed and taxied towards the clearing at the end of the strip which looked like the loading and unloading area. As we approached the clearing we noticed a small group of Vietnamese men in black pyjamas but there was no sign of any Americans or any US Army equipment. The Vietnamese men were glaring at us and showing no signs of welcome whilst in the background I noticed a sudden flurry of activity.

When we asked about this at our next port of call, the American army Lieutenant exclaimed, “Jesus, man ! That’s in VC territory. You were lucky to get out of there”.

In hindsight, I believe the reason we got away with it was because the Viet Cong was just as surprised as we were, and by taking off again without stopping we were gone before they had time to get organised. We didn’t make that mistake again.

We ended up flying 12 sorties that day and arrived back at Vung Tau field well after dark. The last sector was mine and as there had been a power failure on the base I had to land in the dark on the short PSP (perforated steel planking) strip. It had been a long but very interesting day.

You knew when you were hit – it sounded just like an empty beer can hitting the floor. Fortunately, the rounds would usually pass harmlessly through the tail or rear fuselage. On landing, the Loadmaster would carry out an inspection and if no serious damage had been done, he’d simply whack some green tape over the bullet holes and we’d press on heroically. For some reason the Viet Cong didn’t seem to have thought about aiming ahead of a moving target and we were sure hoping no one would tell them. In one instance we were hit in the tail on take off out of a remote strip and my co-pilot, Flg Off Bill Pike, did a rough calculation based on the aircraft’s speed and height, and the speed and time of flight of the bullet, and told me I was very lucky. His calculation suggested the VC soldier had aimed at my head.

There was one occasion, however, when my luck almost ran out. It was probably the closest I ever came to being actually shot down.

Of course the dangers were not always just from enemy action as there was also the occasional risk of being hit by friendly fire. On this occasion, however, we had been despatched to Da Nang in the far north of the country with Caribou A4-173 on a six day detachment. We were a standard crew consisting of Captain, Copilot, Loadmaster and Assistant Loadmaster. Operations near the border into places like Dong Ha were particularly tricky, but the first four days went well, with all sorties flown exactly as planned, which is just the way I liked it. Then the weather turned bad.

The 25th of February 1966 at Da Nang was not a nice day. Monsoonal weather had really set in. There was low cloud, areas of heavy rain and reduced visibility. We managed to complete our first mission to Quang Ngai but the weather was steadily deteriorating. Our second mission to Ba To had to be aborted due to the low cloud base and poor visibility and we had to return to Da Nang with the load. The third mission was to deliver a load of ammunition up north to Khe Sanh, a beleaguered Special Forces camp in hostile territory just south of the border with North Vietnam. The chances of getting into Khe Sanh were slim but the mission was urgent and the lives of American soldiers were at stake.

My copilot Plt Off Dick Cooper and I had flown together quite a bit and had a pretty good idea of what we could and could not do. We felt that, in spite of the low cloud base and the unfriendly territory, we could get into Khe Sanh by flying at tree top level and maximum speed; the theory being that by the time an enemy soldier on the ground hears you coming, grabs his weapon, cocks it and tries to take aim, you have already disappeared behind the trees. It was risky, but as the troops desperately needed the ammunition we felt the risk was justified. However, this technique does not work over flat open country, as Peter Yates and Bill Pike later found out.

They were flying low and fast over rice paddies and unfortunately had the bad luck to fly right over a platoon of enemy soldiers. The soldiers heard the Caribou coming and had plenty of time to aim their weapons and spray the aircraft with small arms fire. The aeroplane took 11 hits with one round severing a rudder cable causing the relevant rudder pedal to drop uselessly to the floor. They were lucky and got away with it, but a valuable lesson was learnt by all.

On another occasion, the Loadmaster, Bob St John, happened to be sitting on an esky behind the two pilots when a round came up through the belly of the aircraft, penetrated the cockpit floor, passed through the bottom of the esky, continued on through the ice inside and stopped when it lodged in the esky lid – a hair’s breadth from the Loadmaster’s backside. Bob extricated the bullet and kept it as a particularly personal souvenir.

Anyway, the flight into Khe Sanh, although fairly hairy, worked out according to plan and we were able to deliver a much needed cargo to a very grateful customer. But having got in, we now had to get out and I had this nagging feeling that everything had been going just a little too easily.

Khe Sanh is surrounded by jungle-covered hills. We had to fly low because of the cloud base and the need to remain visual for accurate navigation but the rugged terrain meant it was impossible to get really low and hug the ground. There were areas where we knew we would be vulnerable to ground fire but there wasn’t much we could do about it. I decided not to go out along the same route we had flown in as any VC or North Vietnamese soldiers would have been alerted by our earlier flight and would be waiting for us on our return.

This may or may not have been a good decision, depending, I guess, on one’s point of view. Be that as it may, I had made my decision and having unloaded the aircraft and picked up a couple of Medevac patients, we took off. I pulled the landing gear and flaps in as quickly as possible and headed out over the hills and valleys keeping as low as I could.

I had full throttle and a speed of around 140 knots when it happened. There was a loud whoomph ! right outside my window. It was so close I not only heard it but felt it as well, and so did the other members of the crew. Initially we weren’t sure whether we’d been hit or not, but the aeroplane continued to handle normally and after checking to make sure no obvious damage had been done, we flew on back to base without further incident.

Although the shock wave shook the aircraft and startled me momentarily, surprisingly, I felt no fear. Of course the adrenalin would have been flowing anyway, but I had always thought that in such a situation the sensation of fear would be uncontrollable. I guess at the time I was too busy to be frightened, but on later reflection it began to sink in just how close we’d come to being blown out of the sky. I don’t know what it was that was fired at us, but whatever it was, it certainly would have been big enough and powerful enough to bring down a Caribou – and at that speed and altitude there would have been no survivors. Whoever fired at us missed. He didn’t miss by much, but thank God he missed. I guess that one just didn’t have my name on it.

The Cow that lost its Parachute.

This story is funny, sad and yet not so sad. As for whether it’s funny or not, I guess it depends on your sense of humour, but it sure was funny the way the Loadmaster described it.

I’m not sure now whether it was Luong Son or Ban Tri, but we had to air drop a live cow in a crate to this particular camp which for one reason or another did not have a useable airstrip.

Anyway, we duly arrived over the drop zone and I made my run in. At the appropriate moment I ordered “Execute ! Execute !” and the Loadmaster let go the load. Out went the crate containing the cow, and according to the Loadmaster, the parachute worked perfectly. The only trouble was, this particular crate must have been badly put together for although the crate came down beautifully by parachute, the floor separated and kept on going with the cow still standing on it.

According to the Loadmaster, it was one of funniest sights he’d ever seen. There was the cow, standing on a small wooden floor like a surf board, hurtling through the air with its nostrils flared, ears flapping in the wind and its tail streaming out behind it. He claims the cow actually enjoyed it, and swears he could see it grinning.

The sad part of course, is that the cow would have eventually hit the ground and been killed instantly. But then it’s perhaps not so sad because the cow was probably going to be slaughtered for beef anyway. At least it died happy and the South Vietnamese soldiers would still have got their steaks. Nevertheless, after that I took care to make sure that this type of incident did not happen again. |

The three most common expressions (or famous last words) in aviation are:

"Why is it doing that?", "Where are we?" and "Oh Shite!"

|

|

[1] Gary is writing his memoirs and this information is taken from that data. |

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward

|

The

original Sky-Rider has been donated to the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney a

The

original Sky-Rider has been donated to the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney a